Debunking the legend of the mouse

OUR COVERAGE:

Part 1: A virtual unknown

Part 2: Against all odds

Part 3: Debunking the legend of the mouse

Part 4: The crusade

Part 5: It's networking

Part 6: A pioneers' reunion

Tech pioneers

The first time I heard about Doug Engelbart I was confused. The invitation for "Engelbart's Unfinished Revolution," a daylong symposium in December at Stanford University, promoted the computer scientist as the inventor of the computer mouse.

"That can't be right," I told my husband. "The mouse was invented at Xerox PARC."

That's the story I'd been told since arriving in Silicon Valley. The legend goes like this: In 1979, Steve Jobs was touring Xerox Corp.'s cutting-edge Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) when he spotted a version of the mouse. He refined the idea and used it in Lisa, forerunner of the Macintosh.

What's left out of the story is that the mouse and a multitude of other personal computing firsts spotted by Jobs on that Xerox PARC tour actually came from Engelbart's lab at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI). The ideas were brought to PARC by Engelbart researchers who started migrating over in the early '70s.

The symposium, organized by Saffo and co-hosted by the Institute for the Future and Stanford University Libraries, whetted my interest in Engelbart's work. I called him and asked for an interview.

"People say, 'Oh, you invented the mouse? You were at Xerox PARC.' And I tell them, 'No, I was at SRI.' "

Douglas Engelbart

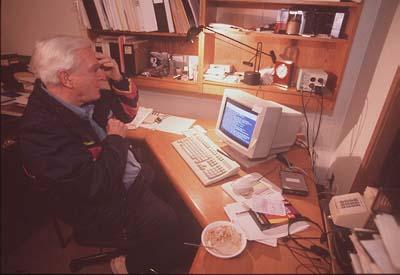

Hesitantly, he agreed to let me tag along and observe a typical Engelbart morning. And so, at 7 a.m., post-gym, Engelbart and I are sitting in his frigid home office. When I point out that a window is open, Engelbart looks sheepish. "I opened it last summer and forgot to shut it."

I bring up the Xerox PARC legend. "Yeah, I bump into that story a lot," he confirms matter-of-factly. "People say, 'Oh, you invented the mouse? You were at Xerox PARC.' And I tell them, 'No, I was at SRI.' "

Engelbart checks the morning e-mail at home in Atherton. To the left

of the keyboard is a chord keyset, which allows the user to type

commands in a shorthand code.

He is eating granola. Every morning Engelbart breakfasts with his computer, a ritual he started after Ballard, his wife of 46 years, died about a year-and-a-half ago.He still lives in the same Atherton home they purchased for $76,000 in 1968. It is comfortable but lacking the opulence characteristic of Silicon Valley's trophy houses.

"Doesn't it bother you that Steve Jobs and others got fabulously wealthy off your work and they get the credit?" I ask.

"I didn't do this to be famous," Engelbart says in his soft-spoken, understated manner. "And how much money can you give to a guy who's just doing his job?"

If Engelbart was bitter about his life, he hid it from his three daughters and son. They never realized until they were adults that their father was responsible for revolutionizing technology. The only clue in their home was the teletype Engelbart installed in the '60s.

"He was telecommuting as early as possible," says Christina Engelbart, associate director of the Bootstrap Institute, her father's Fremont-based think tank. She describes a warm, fun-loving family man, who enjoyed organizing neighborhood games. "All the kids loved him. He'd take us hiking and canoeing," she recalls.

Engelbart's official biography, written by Christina, notes that Engelbart would help his wife fall asleep by delivering science lectures, and he'd make up science-fiction tales to entertain his children, and now for his nine grandchildren.

Engelbart boots up his computer. The modest-looking PC is networked to an extremely sophisticated computing system that you can't buy in the stores - a much-refined and advanced version of Augment, the system he debuted in 1968 and initially named NLS, for oNLine Systems. (Engelbart's mission is to augment human intelligence, hence the name.)

Engelbart is the first to admit he's a lousy salesman of his own ideas, a serious handicap for a revolutionary. He manipulates the screen with a mouse in his right hand, while typing commands with his left hand on something that looks like five piano keys, called a chord keyset.

"I can 'talk' to the computer at the same time that I'm 'pointing,' " he explains. Although Engelbart spent the next 10 minutes describing how this device works, I never did understand him. He's the first to admit he's a lousy salesman of his own ideas, a serious handicap for a revolutionary.

The chord keyset, I subsequently learned, is ingenious. It's an auxiliary to a standard keyboard, allowing you to deliver commands in a shorthand code. If your right hand is busy using the mouse, your left hand can keep working.

"It needs to be much easier to use before I'd buy it," I tell him.

Engelbart's easygoing manner vanishes. "I hate the term 'user-friendly,' " says the guy credited with virtually inventing the concept. "People balk if they have to learn a different way of doing something."

The keyset has never been turned into a viable commercial product - which drives Engelbart nuts. To Engelbart, the fact that many of his innovations are user-friendly is incidental. He believes the commercial world's fixation on user-friendliness has seriously slowed down the computer revolution. Instead of developing the best tools, marketers want products that are easy to use, even if they aren't the most productive. So consumers are sold inferior products. He sighs, "This is what I came up against in the '70s."